The Life Saving Service on the Ohio: a Short History

It may look peaceful now, but the Falls of the Ohio were once the most dangerous part of the Ohio River. This stretch consisted of 2.5 miles of whitewater rapids that split river navigation in half. It was the only obstruction in the Ohio River, all the way from Pittsburgh to the Mississippi.

These rapids were formed by the fossilized remains of an ancient coral reef that was so big and resistant to the normal erosion of limestone in the water that it changed the shape of the river. For millennia, this served as a landmark and meeting place for people and animals. However, when Europeans began colonizing this land, they would use three natural “chutes” that they could navigate to pass through the Falls safely – and quickly, which is where the term “chute” or “shoot” comes from.

Engraving of a map of the Ohio River with the Falls of the Ohio and its chutes visible.

Eventually, the city grew up around the Falls. The river was an important part of daily life, whether it was for work or travel. The busy, perilous river meant that many people were exposed to the danger of the Falls of the Ohio every day.

The First Official Lifesaving Crew

The story of the Mayor Andrew Broaddus actually starts in 1876 when a skiff belonging to the steam towboat the John Gilmore capsized. Three men were inside, who were seen clinging to it and calling for help. Nearby, two workers at a floating coal dock noticed the emergency. Billy Devan and Jack Gillooly luckily had a skiff themselves tied to the coal dock. They used it to rush toward the foot of the Falls of the Ohio to rescue the three men just in time.

The next week, Gillooly was not around when Devan saw yet another accident. He called out to John Tully, a local fisherman who was familiar navigating the Falls, who joined Devan to help.

The three of them thus banded together as the “Falls Heroes,” a name given to them by a local newspaper columnist.

Life Saving Station Number 10

After this, advocacy for an official lifesaving station began. People were skeptical in Washington, because there were no inland lifesaving stations so far. So in May 1881, two officials came to the Falls to inspect the situation. Although they initially deemed it a “folly,” after riding in the chute with the Falls Heroes in the skiff that had become their lifeboat, they realized that there was a genuine need.

The first idea was for a station to be built high up on the Falls of the Ohio, with signal lights. This was deemed too expensive, and so a floating lifesaving station with a watchtower was proposed. Life Saving Station #10 officially began service in 1881, with Billy Devan as the keeper. The boats in the 1881 station were named “Reckless” and “Ready.”

Daily Life at the Station

The rescuers at the Life Saving Station were known as “boatmen,” rather than the “surfmen” of coastal Life Saving Stations. Their skills were unique to the circumstances of Ohio River Rescue, and their work was described as “routinely arduous, extremely boring…punctuated by the sudden bursts of peril, even sheer terror, of plunging into roaring whitewater falls and over dams in open boats.”

The Life Saving Station, circa 1900

The job consisted of long watches in the lookout tower, first with a spyglass and later with binoculars. They would spend hours scanning the river for people in trouble or threats to public safety. To make sure they were awake, a lookout was required to punch a timeclock every 15 minutes.

The Second Station

The 1881 Life Saving Station #10 was made of wood, which quickly rotted away. By 1902, a new boat was desperately needed. A new one was delivered to the wharf on November 6 of that year, and the original 1881 station was sold for $226 to become the wharf boat at Patriot, Indiana. In 1908, the station got its first motorized powerboat, built upriver at the Howard Shipyard.

Billy Devan died in 1911. Afterward, John Gillooly was put in charge. In this next stage, technological advancements came quickly. A telephone was installed in 1911. However, Gillooly (also known as “Captain Jack”) was skeptical of having a radio onboard the lifesaving station. After the Titanic sank, a bill went up in Congress to get radios on all lifesaving stations. However, because this lifesaving station was an exception anyway, Gillooly successfully avoided getting a radio onboard until after the 1937 Louisville flood.

A number of remarkable rescues and narrow escapes ensued over the next few years. In 1912, ice clogged the Ohio River. The force of the ice traveling downriver brought several huge boats with it, and almost took the Life Saving Station with it. The ropes were really strained, “quivering like violin strings,” and threatened to break. The boat was damaged and the idea of a steel hulled lifesaving station began to percolate. Then, in 1913, the crew traveled upriver to help with flooding in the Cincinnati area. They saved approximately 500 families around Dayton, Kentucky. In 1914, the steamer Queen City sank at the Falls on the way to New Orleans for Mardi Gras and 215 people were saved, many of them notable people from large cities. These influential passengers helped persuade Washington DC to make this lifesaving station part of the Coast Guard officially.

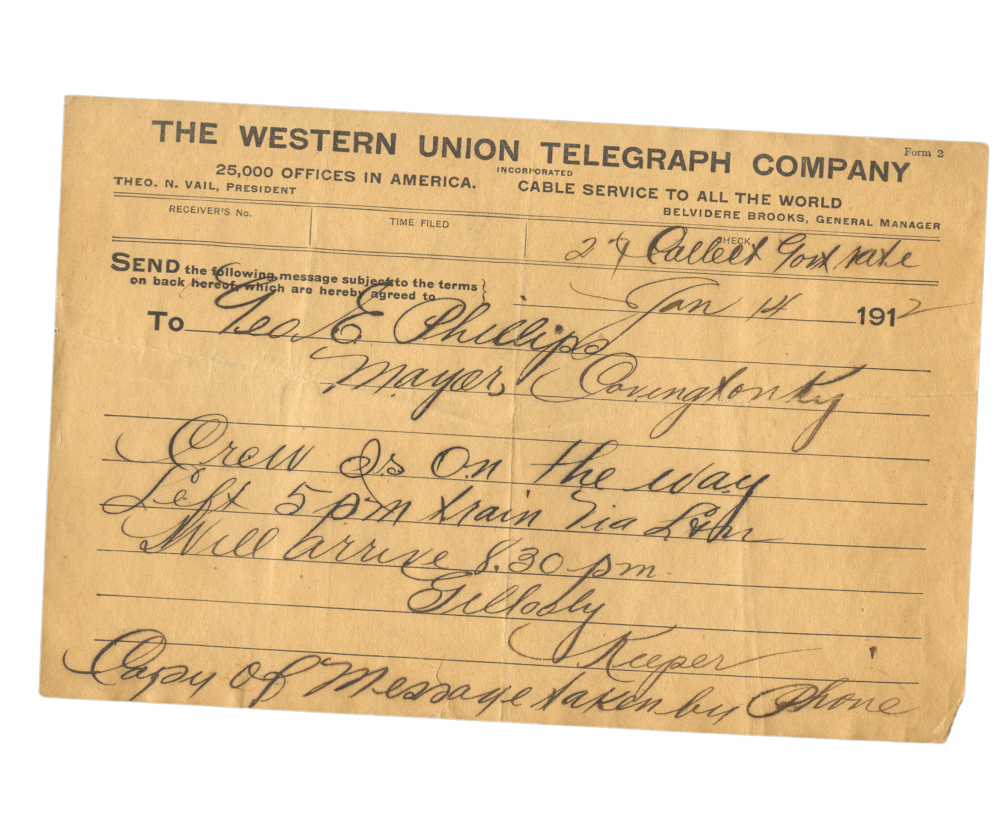

This 1912 telegram was sent by John Gillooly when the crew went up to Dayton to rescue 500 families.

Part of the Coast Guard

By 1915, a lot of the things about Life Saving Station #10 had become outdated: the technology, the equipment, and the pay structure. The young and agile lifesavers needed could not afford to work for the low wages and lack of pension that the Life Saving Station offered. Furthermore, Presidents Taft, Roosevelt, and Wilson were also big on government efficiency, so lots of outdated departments having to do with old tech like steamboats were closed and folded into other governmental departments and agencies.

In 1915, the Life Saving Service officially became the Coast Guard, and Life Saving Station #10 became the Coast Guard Life Saving Station – Louisville.

The Last Lifesaving Station

In 1929, the Coast Guard finally got a boat with a steel hull. This vessel, built in Dubuque, Iowa, and named the Louisville, was the last Life Saving Station to arrive at the wharf. It’s been at this spot since 1936, when the construction of the 2nd Street Bridge made it necessary to move. This boat had all the latest 1920s technology: two skiffs, a surf boat and a motorboat.

The tumultuous events of the 1930s and 1940s affected the station’s daily operations and mission. With Prohibition, the Station’s mission took a bit of a turn. In addition to daring rescues, the Coast Guard was also charged with enforcing the Volstead Act. This means that the Coast Guard servicemen here were charged with patrolling the many small and remote islands in the area to find illicit distilleries. During World War II, the lookout kept an eye on the river for spy activity and other operations meant to disrupt American trade.

By the 1970s, the station was decommissioned due to budget cuts. It was then renamed the Mayor Andrew Broaddus and later converted into offices for another old boat that had recently been rescued: the Belle of Louisville.